\

ALL-BLACK TOWNS

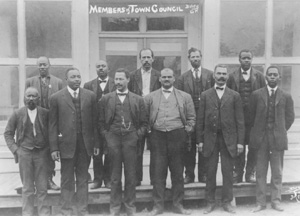

Town council, Boley, Oklahoma, ca. 1907–10

Town council, Boley, Oklahoma, ca. 1907–10

View larger African Americans left the South for the "promised land" of the West in ever-increasing numbers after the Civil War. Economic hardship, racial violence, and intolerance prompted this vast migration from states such as Mississippi, Louisiana, Tennessee, Texas, and Arkansas. With leadership from Pap Singleton and Henry Adams, the "Exodusters" settled mainly in Kansas in 1879–80, though the movement had began a few years earlier and lasted into the next decade. The opportunity to own land attracted many of these people to the Great Plains. Reports directed back to the South claimed that landownership was a simple and cheap prospect.

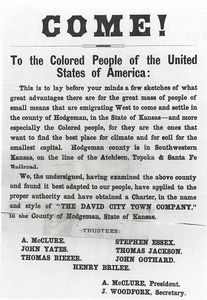

By 1881 African Americans emigrants had established twelve agricultural colonies in Kansas: Nicodemus, Hodgeman, Morton City, Dunlap, Kansas City–area Colony, Parsons, Wabaunsee, Summit Township, Topeka-area Colony, Burlington, Little Coney, and the Daniel Votaw Colony. Another settlement, the Singleton Colony, seems to have never really been a viable community. Many of the other colonies lasted only a few years. The town of Nicodemus, on the other hand, founded a few years before the large exodus, prospered into the twentieth century. African Americans also established colonies in Nebraska, including the town of Dewitty. They migrated to western New Mexico, too, creating settlements such as Blackdom and Dora. Oliver Toussaint Jackson established the settlement of Dearfield, Colorado, in 1910, one of the last African American Plains agricultural communities. Many African Americans dispersed elsewhere throughout the Plains; most worked the land like their white counterparts.

During a fifty-five-year period following the end of the Civil War, African Americans built more than fifty identifiable communities in Oklahoma. Some sprouted and quickly vanished; others still survive. Achieving freedom after the Civil War, former slaves of the Cherokees, Creeks, Seminoles, Chickasaws, and Choctaws also formed towns in Indian Territory. When the U.S. government allotted land to individual Native Americans, most Indian "freedman" chose land next to other African Americans. Their farming communities sheltered self-governed economic and social institutions, including businesses, schools, and churches. Enterprising businessmen set up every imaginable kind of business, including publishing concerns whose newspapers advertised in the South for settlers.

More African Americans settled in Oklahoma Territory with the land run of 1889, which ordered "free land" to non-Indians. E. P. McCabe, former state auditor of Kansas, helped found the all-black town of Langston. By means of the Langston City Herald, which his traveling agents circulated around the South, he and other leaders hoped to bring in large numbers of African Americans whose growing political power would secure their prosperity and safety. McCabe never accomplished his goal of creating an African American state. Nevertheless, dozens of black communities sprouted and flourished in the rich topsoil of the new territory and, after 1907, the new state.

In Oklahoma and Kansas, African Americans lived relatively free from the prejudices and brutality common in racially mixed communities of the Midwest and the South. Cohesive all-black settlements offered residents the security of depending on neighbors for financial assistance and the economic opportunity provided by access to open markets for their crops.

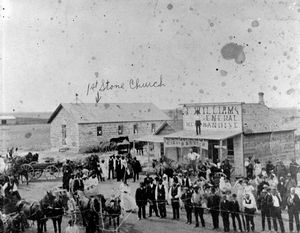

Marshalltown, North Fork Colored, Canadian Town, and Arkansas Colored existed as early as the 1860s in Indian Territory. Other Indian Territory towns that no longer exist include Sanders, Mabelle, Wiley, Homer, Huttonville, Lee, and Rentie. Among the Oklahoma Territory towns that no longer exist are Lincoln, Cimarron City, Bailey, Zion, Emanuel, Udora, and Douglas in old Oklahoma Territory. Surviving towns include Boley, Brooksville, Clearview, Grayson, Langston, Lima, Redbird, Rentiesville, Summit, Taft, Tatums, Tullahassee, and Vernon. Boley, the largest and most renowned of these was twice inspected by African American educator Booker T. Washington, who lauded the town in Outlook Magazine in 1908.

Immediately after statehood in 1907 the Oklahoma legislature passed Jim Crow laws, and many African Americans became disenchanted with the new state. A large contingent relocated to western Canada, forming colonies such as Amber Valley, Alberta, and Maidstone, Saskatchewan. Another exodus of African Americans from the United States occurred with the "Back to Africa" movements of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. A large group of Oklahomans joined the illfated Chief Sam expedition to Africa. Other Plains African Americans migrated to colonies in Mexico.

The collapse of the American farm economy in the 1920s and the advent of the Great Depression in 1929 spelled the end for most all-black communities. The all-black towns were, for the most part, small agricultural centers that gave nearby African American farmers a market for their cotton and other crops. The Depression devastated these towns, and residents moved west or migrated to metropolises where jobs might be found. Black towns dwindled to only a few residents.

As population dwindled, so too did the tax base. In the 1930s many railroads failed, isolating small towns from regional and national markets. This spelled the end of many of the black towns. During the Depression, whites denied credit to African Americans, creating an almost impossible situation for black farmers and businessmen. Even Boley, one of the most successful towns, declared bankruptcy in 1939. Today, only a few all-black towns survive, but their legacy of economic and political freedom is well remembered.

Larry O'Dell

Oklahoma Historical Society

Crockett, Norman. The Black Towns. Lawrence: Regents

Press of Kansas, 1979.

Hamilton, Kenneth Marvin. Black

Towns and Profit: Promotion and Development in the

Trans-Appalachian West, 1877–1915. Urbana: University

of Illinois Press, 1991.

Taylor, Quintard. In Search of the

Racial Frontier: African Americans in the American West,

1528–1990. New York: W. W. Norton, 1998.

XML: egp.afam.006.xml

777 &&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&

http://digital.library.okstate.edu/encyclopedia/entries/A/AL009.html

| Table of Contents | Search All Entries | Home |

ALL-BLACK TOWNS

The All-Black towns of Oklahoma represent a unique chapter in American history. Nowhere else, neither in the Deep South nor in the Far West, did so many African American men and women come together to create, occupy, and govern their own communities. From 1865 to 1920 African Americans created more than fifty identifiable towns and settlements, some of short duration and some still existing at the beginning of the twenty-first century.All-Black towns grew in Indian Territory after the Civil War when the former slaves of the Five Civilized Tribes settled together for mutual protection and economic security. When the United States government forced American Indians to accept individual land allotments, most Indian "freedmen" chose land next to other African Americans. They created cohesive, prosperous farming communities that could support businesses, schools, and churches, eventually forming towns. Entrepreneurs in these communities started every imaginable kind of business, including newspapers, and advertised throughout the South for settlers. Many African Americans migrated to Oklahoma, considering it a kind of "promise land."

When the Land Run of 1889 opened yet more "free" land to non-Indian settlement, African Americans from the Old South rushed to newly created Oklahoma. E. P. McCabe, a former state auditor of Kansas, helped found Langston and encouraged African Americans to settle in that All-Black town. To further his cause, McCabe established the Langston City Herald and circulated it, often by means of traveling agents, throughout the South. McCabe hoped that his tactics would create an African American political power block in Oklahoma Territory. Other African American leaders had a vision of an All-Black state. Although this dream was never realized, many All-Black communities sprouted and flourished in the rich topsoil of the new territory and, after 1907, the new state.

In these towns African Americans lived free from the prejudices and brutality found in other racially mixed communities of the Midwest and the South. African Americans in Oklahoma and Indian Territories would create their own communities for many reasons. Escape from discrimination and abuse would be a driving factor. All-Black settlements offered the advantage of being able to depend on neighbors for financial assistance and of having open markets for crops. Arthur Tolson, a pioneering historian of blacks in Oklahoma, asserts that many African Americans turned to "ideologies of economic advancement, self-help, and racial solidarity."

Marshalltown, North Fork Colored, Canadian Colored, and Arkansas Colored existed as early as the 1860s in Indian Territory. Other Indian Territory towns that no longer exist include Sanders, Mabelle, Wiley, Homer, Huttonville, Lee, and Rentie. Among the Oklahoma Territory towns no longer in existence are Lincoln, Cimarron City, Bailey, Zion, Emanuel, Udora, and Douglas. Towns that still survive are Boley, Brooksville, Clearview, Grayson, Langston, Lima, Red Bird, Rentiesville, Summit, Taft, Tatums, Tullahassee, and Vernon. The largest and most renowned of these was Boley. Booker T. Washington, nationally prominent African American educator, visited Boley twice and even submitted a positive article on the town to Outlook Magazine in 1908.

The passage of many Jim Crow laws by the Oklahoma Legislature immediately after statehood caused some African Americans to become disillusioned with the infant state. During this time Canada promoted settlement and, although the campaign focused on whites, a large contingent of African Americans relocated to that nation's western plains, forming colonies at Amber Valley, Alberta, and Maidstone, Saskatchewan. Another exodus from Oklahoma occurred with the "Back to Africa" movements of the early twentieth century. A large group of Oklahomans joined the ill-fated Chief Sam expedition to Africa. A number of other African Americans migrated to colonies in Mexico.

White distrust also limited the growth of these All-Black towns. As early as 1911 whites in Okfuskee County attempted to block further immigration and to force African Americans into mixed but racially segregated communities incapable of self-support. Several of these white farmers signed oaths pledging to "never rent, lease, or sell land in Okfuskee County to any person of Negro blood, or agent of theirs; unless the land be located more than one mile from a white or Indian resident." To further stem the black migration to eastern Oklahoma a similar oath was developed to prevent the hiring of "Negro labor."

Events of the 1920s and 1930s spelled the end for most black communities. The All-Black towns in Oklahoma were, for the most part, small agricultural centers that gave nearby African American farmers a market. Prosperity generally depended on cotton and other crops. The Great Depression devastated these towns, forcing residents to go west and north in search of jobs. These flights from Oklahoma caused a huge population decrease in black towns.

As people left, the tax base withered, putting the towns in financial jeopardy. In the 1930s many railroads failed, isolating small towns in Oklahoma from regional and national markets. As a result, many of the black towns could not survive. During lean years whites would not extend credit to African Americans, creating an almost impossible situation for black farmers and businessmen to overcome. Even one of the most successful towns, Boley, declared bankruptcy in 1939. Today, only thirteen All-Black towns still survive, but their legacy of economic and political freedom is well remembered.

SEE ALSO: AFRICAN AMERICANS, BOLEY, BROOKSVILLE, CLEARVIEW, FREEDMEN, LANGSTON, LINCOLN CITY, EDWARD McCABE, RED BIRD, RENTIESVILLE, SEGREGATION, SETTLEMENT PATTERNS, SUMMIT, TAFT, TATUMS, TULLAHASSEE, VERNON

BIBLIOGRAPHY: Black Dispatch (Oklahoma City), 8 March 1923. Norman Crockett, The Black Towns (Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1979). Norman Crockett, "Witness to History: Booker T. Washington Visits Boley," The Chronicles of Oklahoma 67 (Winter 1989-90). Kenneth Lewallan, "Chief Alfred Sam: Black Nationalism on the Great Plains, 1913-14," Journal of the West 16 (January 1977). Bruce Shepard, "North to the Promised Land: Black Migration to the Canadian Plains," The Chronicles of Oklahoma 66 (Fall 1988).

Larry O'Dell

© Oklahoma Historical Society

*********************************************************************************

Edward Preston McCabe emerged as the father of the Oklahoma all-black town movement. McCabe, a Republican, served as Kansas State Auditor in the State of Kansas from 1882 – 1886. He once lived in Nicodemus, Kansas, a seminal all-black town.

On April 22, 1889, McCabe joined 50,000 homesteaders in the Oklahoma Land Run. This was the opening of “Oklahoma Territory,” Indian Country land appropriated by the federal government for general settlement. On these acres of aspiration, McCabe hoped to germinate an all-black state.

In 1890, McCabe called on President Benjamin Harrison to press the case for an all-black state. McCabe believed that a self-governing, all-black enclave would offer his people the freedom and opportunity routinely denied them elsewhere in America. In the end, his entreaties failed.

McCabe soldiered on. He founded Langston, Oklahoma, on October 22, 1890, and established the McCabe Townsite Company and the Langston City Herald newspaper to promote its growth and development. McCabe developed recruiting bulletins and hired agents for his Oklahoma “boosterism” efforts.

McCabe drew throngs to unspoiled Oklahoma—“land of the red people” in the Choctaw language. These pioneers founded more than fifty all-black towns in Oklahoma.

Despite an auspicious beginning, the all-black town movement crested between 1890 and 1910. Oklahoma attained statehood in 1907 and, with it, roundly embraced “Jim Crow.” By 1910, the American economy had shifted from agricultural to industrial-based. These developments (i.e., the rise of racism; the demise of agrarianism) doomed many of these unique, historic oases. The few that remain serve as monuments to the human spirit.

Oklahoma’s pioneering black forefathers and foremothers planted the trees under whose shade we now sit. The value of their legacy to us—the likes of Boley, Clearview, Langston, Red Bird, Rentiesville, Taft, Tatums, Tullahassee—is inestimable. We owe them a tremendous debt of gratitude.

Oklahoma’s all-black towns, some still viable, others long gone, represent a significant aspect of the African-American struggle for freedom, justice, and equality. This rich history should be resurrected, reclaimed, and remembered.

Photo of Langston, Oklahoma by George Thomas

Posted 06.05.10

Prominently in Kansas,

and then principally in Oklahoma, towns founded by black trailblazers

swelled in the post-Reconstruction era. Black Southern migrants,

“Exodusters,” formed their own rural, frontier communities. They sought

economic opportunity, full citizenship rights, and self-governance:

socioeconomic uplift, sprinkled with a generous measure of hope.

In addition to black homesteaders, some persons of African ancestry

prospered because of Native American affiliations—through the bonds of

slavery, by blood, and in affinity relations. All-black colonies

populated by these “Natives” sprang up in Indian Territory, the eastern

portion of modern-day Oklahoma.Edward Preston McCabe emerged as the father of the Oklahoma all-black town movement. McCabe, a Republican, served as Kansas State Auditor in the State of Kansas from 1882 – 1886. He once lived in Nicodemus, Kansas, a seminal all-black town.

On April 22, 1889, McCabe joined 50,000 homesteaders in the Oklahoma Land Run. This was the opening of “Oklahoma Territory,” Indian Country land appropriated by the federal government for general settlement. On these acres of aspiration, McCabe hoped to germinate an all-black state.

In 1890, McCabe called on President Benjamin Harrison to press the case for an all-black state. McCabe believed that a self-governing, all-black enclave would offer his people the freedom and opportunity routinely denied them elsewhere in America. In the end, his entreaties failed.

McCabe soldiered on. He founded Langston, Oklahoma, on October 22, 1890, and established the McCabe Townsite Company and the Langston City Herald newspaper to promote its growth and development. McCabe developed recruiting bulletins and hired agents for his Oklahoma “boosterism” efforts.

McCabe drew throngs to unspoiled Oklahoma—“land of the red people” in the Choctaw language. These pioneers founded more than fifty all-black towns in Oklahoma.

Despite an auspicious beginning, the all-black town movement crested between 1890 and 1910. Oklahoma attained statehood in 1907 and, with it, roundly embraced “Jim Crow.” By 1910, the American economy had shifted from agricultural to industrial-based. These developments (i.e., the rise of racism; the demise of agrarianism) doomed many of these unique, historic oases. The few that remain serve as monuments to the human spirit.

Oklahoma’s pioneering black forefathers and foremothers planted the trees under whose shade we now sit. The value of their legacy to us—the likes of Boley, Clearview, Langston, Red Bird, Rentiesville, Taft, Tatums, Tullahassee—is inestimable. We owe them a tremendous debt of gratitude.

Oklahoma’s all-black towns, some still viable, others long gone, represent a significant aspect of the African-American struggle for freedom, justice, and equality. This rich history should be resurrected, reclaimed, and remembered.

Photo of Langston, Oklahoma by George Thomas

Related

Articles + Videos + AudioBrowse a Category

Comment

Magazine | Okiecentric

%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%| MIGRATION TO KANSAS- | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

88000000000000000000

informat0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

|

|||||

|

|||||

Kansas State Historical Society, Copy and Reuse Restrictions Apply

|

|

| Reverend Daniel Hickman | |

| African Americans tended to migrate to the West in a predictable pattern. Sometimes, entire towns relocated together, encouraged to move by homestead associations or promoters. Of the six African Americans who organized the Nicodemus Town Company, five were natives of Kentucky. President W.H. Smith hailed from Tennessee. Reverend Daniel Hickman led one of the first groups of settlers from Kentucky to Nicodemus. | |

Prominently in Kansas,

and then principally in Oklahoma, towns founded by black trailblazers

swelled in the post-Reconstruction era. Black Southern migrants,

“Exodusters,” formed their own rural, frontier communities. They sought

economic opportunity, full citizenship rights, and self-governance:

socioeconomic uplift, sprinkled with a generous measure of hope.

In addition to black homesteaders, some persons of African ancestry

prospered because of Native American affiliations—through the bonds of

slavery, by blood, and in affinity relations. All-black colonies

populated by these “Natives” sprang up in Indian Territory, the eastern

portion of modern-day Oklahoma.Edward Preston McCabe emerged as the father of the Oklahoma all-black town movement. McCabe, a Republican, served as Kansas State Auditor in the State of Kansas from 1882 – 1886. He once lived in Nicodemus, Kansas, a seminal all-black town.

On April 22, 1889, McCabe joined 50,000 homesteaders in the Oklahoma Land Run. This was the opening of “Oklahoma Territory,” Indian Country land appropriated by the federal government for general settlement. On these acres of aspiration, McCabe hoped to germinate an all-black state.

In 1890, McCabe called on President Benjamin Harrison to press the case for an all-black state. McCabe believed that a self-governing, all-black enclave would offer his people the freedom and opportunity routinely denied them elsewhere in America. In the end, his entreaties failed.

McCabe soldiered on. He founded Langston, Oklahoma, on October 22, 1890, and established the McCabe Townsite Company and the Langston City Herald newspaper to promote its growth and development. McCabe developed recruiting bulletins and hired agents for his Oklahoma “boosterism” efforts.

McCabe drew throngs to unspoiled Oklahoma—“land of the red people” in the Choctaw language. These pioneers founded more than fifty all-black towns in Oklahoma.

Despite an auspicious beginning, the all-black town movement crested between 1890 and 1910. Oklahoma attained statehood in 1907 and, with it, roundly embraced “Jim Crow.” By 1910, the American economy had shifted from agricultural to industrial-based. These developments (i.e., the rise of racism; the demise of agrarianism) doomed many of these unique, historic oases. The few that remain serve as monuments to the human spirit.

Oklahoma’s pioneering black forefathers and foremothers planted the trees under whose shade we now sit. The value of their legacy to us—the likes of Boley, Clearview, Langston, Red Bird, Rentiesville, Taft, Tatums, Tullahassee—is inestimable. We owe them a tremendous debt of gratitude.

Oklahoma’s all-black towns, some still viable, others long gone, represent a significant aspect of the African-American struggle for freedom, justice, and equality. This rich history should be resurrected, reclaimed, and remembered.

Photo of Langston, Oklahoma by George Thomas

Related

Articles + Videos + AudioDISCOVER > general

general > american

- American Airlines and Tulsa's Vision (2) for a Future in Aerospace

- Oklahoma Makes the Grade in Indian Education

- 2013 African-American High School History Bowl

- Paul Harvey Makes a Comeback

- Hello, My Name Is...

- Everybody's All-American

- The Okie Weekly Reader, All Shook Up Edition

- Oklahoma to Advance Drone Technology

- The Okie Weekly Reader, Wild Horse Chase Edition

- Peeling in the Years

- A Portis Reader

- Oklahoma Indians are Idle No More

- Article

- Video

- Audio

- Photo

Comment

777777777777777777777777777777777777777777777777777777777777777777777777777777777777777

|

||||

|

||||

Kansas State Historical Society, Copy and Reuse Restrictions Apply

|

|||

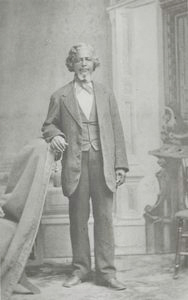

| Benjamin "Pap" Singleton | |||

| Benjamin "Pap" Singleton (1809-92) was born a slave in Nashville, Tennessee and lived as a fugitive in Detroit. After the Civil War, he returned to Tennessee to establish an independent black society. However, racist laws and practices inhibited African Americans from purchasing land within the state. Therefore, working with W. A. Sizemore, Columbus Johnson, and several other former slaves, Singleton promoted the migration of African Americans to Kansas. From 1877 to 1879, he and his associates led several hundred migrants. | |||

|

||||

|

||||

Kansas State Historical Society, Copy and Reuse Restrictions Apply

|

|

| David City Colony | |

| African Americans were attracted to Kansas because of its abolitionist roots, and they were eligible to settle there under the terms of the 1862 Homestead Act. The largest number of black settlers came to Kansas from Kentucky and Tennessee between 1877 and 1880. They became known as Exodusters. Several black settlements sprang up in Kansas. Among them were Singleton - from the name of the Exodusters' leader - in Cherokee County, Morton City in Edwards County, Hodgeman Colony and David City Colony in Hodgeman County, and Dunlap in Morris County. | |

|

||||

|

||||

Kansas State Historical Society, Copy and Reuse Restrictions Apply

|

|

| David City Colony | |

| African Americans were attracted to Kansas because of its abolitionist roots, and they were eligible to settle there under the terms of the 1862 Homestead Act. The largest number of black settlers came to Kansas from Kentucky and Tennessee between 1877 and 1880. They became known as Exodusters. Several black settlements sprang up in Kansas. Among them were Singleton - from the name of the Exodusters' leader - in Cherokee County, Morton City in Edwards County, Hodgeman Colony and David City Colony in Hodgeman County, and Dunlap in Morris County. | |

&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&

|

|||||

|

|||||

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [HABS, KANS,33-NICO,1-6]

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Early Homestead in Nicodemus | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| During the Civil War, the African-American population of Kansas increased from just 627 in 1861 to over 12,000 in 1865. Some white Kansans expressed concern. Richard Cordley, a white abolitionist, dismissed their fears: "The negroes are not coming. They are here. They will stay here. They are American born. They have been here for more than two hundred and fifty years.... It is not for us to say whether they will be our neighbors or not.... It is only for us to say what sort of neighbors they shall be, and whether we will fulfill our neighborly obligations" Richard Cordley, Pioneer Days in Kansas (New York: The Pilgrim Press, 1903). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666666 |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

No comments:

Post a Comment